When forests burn, the first images that come to mind are destruction, smoke, and loss. Yet wildfires are becoming more frequent and intense across the world, forcing us to rethink not only how we respond, but how we rebuild. Instead of treating the aftermath as waste to be cleared and forgotten, a circular approach asks a different question: what if the materials left behind could help restore the land itself? By reusing safe organic debris, rebuilding soil with compost and biochar, and supporting nature‑based recovery, communities can turn post‑fire landscapes into opportunities for regeneration. This shift — from a linear “clean up and throw away” mindset to a circular, restorative one — offers a path where recovery strengthens ecosystems rather than depleting them, and where renewal begins in the ashes.

What happens after a wildfire

When wildfires occur—whether driven by dry weather or human activity—the landscape is left scarred and extremely vulnerable. Animals either flee long distances or perish, vegetation is completely destroyed, and the soil loses its protective cover. With this layer gone, nutrients in the soil are exposed to the air and can be further depleted or burned off by lingering heat and smoke. As a result, the ground becomes dry, unstable, and highly prone to erosion.

Soil damage

The intense heat of a wildfire consumes leaf litter and the nutrient‑rich layer of topsoil, stripping away the organic matter that supports new plant growth. This loss of carbon and essential nutrients undermines the soil’s natural fertility, leaving it far less able to sustain seedlings and young plants. At the same time, fire damages root systems and the delicate network of soil organisms that help retain moisture and cycle nutrients, so the ground becomes drier and less biologically active.

Without roots and organic matter to bind it, the soil’s structure breaks down, and the surface becomes loose and unstable. Wind and rain can then carry this loosened topsoil away, eroding the seed bank and the microbial communities that are vital for recovery. As a result, natural regrowth is slowed and patchy, and any human‑led restoration efforts become more complex and costly because they must rebuild both the physical and biological foundations of the soil.

Wildlife habitat loss

The most obvious devastation of a wildfire is the sudden loss of food and shelter. Once‑bustling habitats are left eerily bare as trees, shrubs, and understory that animals rely on for breeding, cover, and food are consumed in minutes. Insects and small mammals lose hiding places, birds lose nesting sites, and seasonal food sources vanish, leaving the landscape exposed and forcing species into a desperate scramble for survival.

Short‑term chaos often becomes a long‑term crisis. Fast‑moving animals may escape, but slower, younger, or burrowed species often perish, and survivors face reduced breeding success and higher mortality. Wildfires cause extinction risk for at least 1,660 animal species in the world. Large, burned patches fragment continuous habitat, isolating populations and hindering movement, mating, and genetic exchange. Over the years, this favors opportunistic or invasive species and reshapes the community, producing a transformed ecosystem that can take decades to recover without active restoration and careful land management.

Human displacement

When fires sweep through a town, the first human cost is sudden and disorienting: people forced to leave everything behind with minutes to spare. Homes, treasured belongings, and familiar streets can be damaged or lost, turning private lives into temporary shelters and crowded relief centers. That abrupt upheaval fractures daily routines—children lose their classrooms, workers lose their jobs, and families lose the small, steady comforts that make a place feel like home. Even after the flames die down, uncertainty lingers about where to live, how to replace documents and possessions, and whether rebuilding is even possible.

Beyond the immediate loss of shelter, smoke and ash reach far beyond the burn line and quietly harm health and well-being. Prolonged exposure brings coughing, sore eyes, and breathing problems, and it weighs heavily on those already vulnerable—young children, older adults, and people with chronic illnesses. The economic ripple effects deepen the strain: farms, tourism, and local businesses can be devastated, incomes vanish, and the cost of recovery piles up. Together, these pressures create long‑term stress, grief, and mental‑health burdens for communities, even as neighbors and volunteers rally to help one another rebuild.

Circular solutions for wildfire recovery

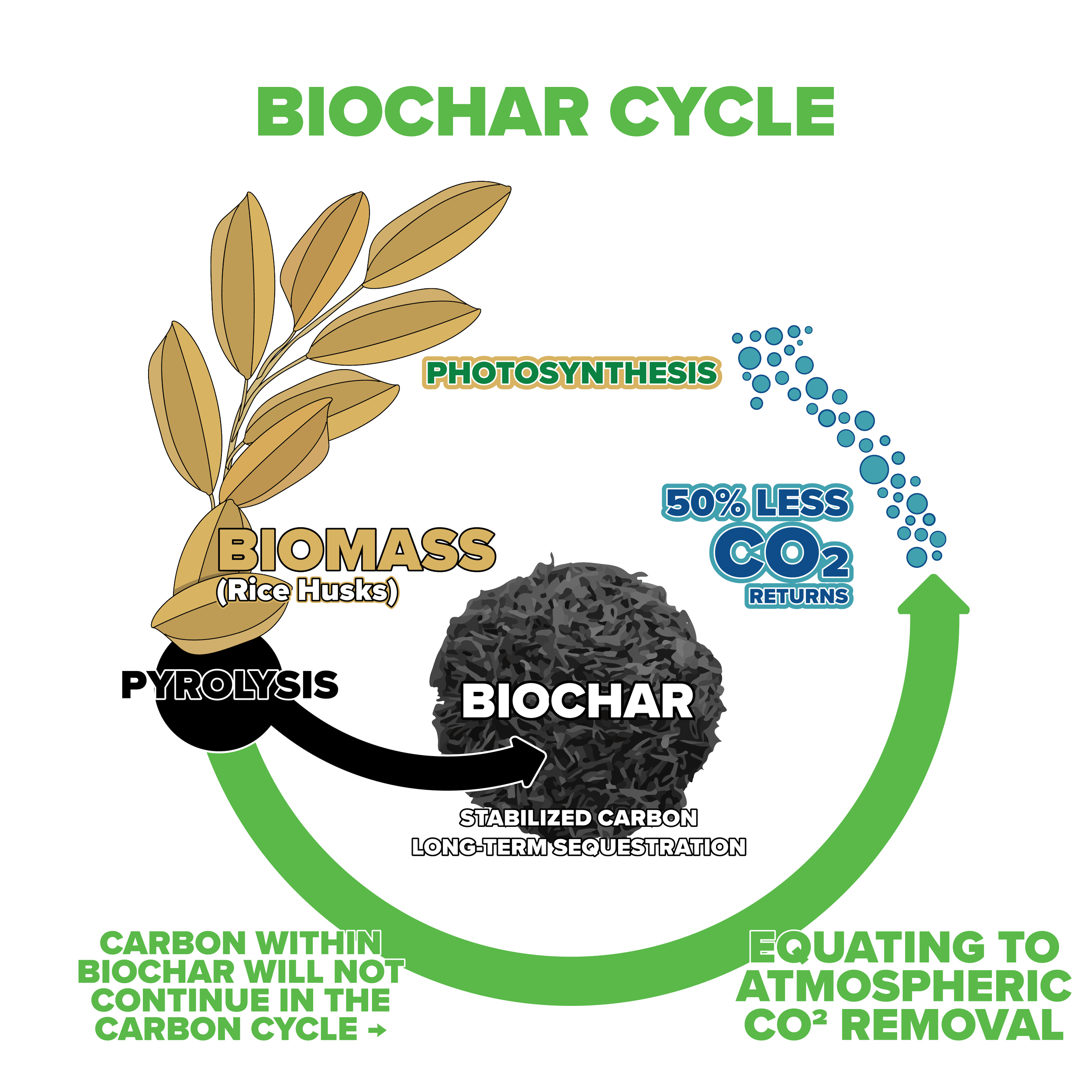

Biochar from burned biomass

Wildfires leave charred wood and hazardous fuel behind, which can be salvaged. These waste products can be converted into biochar through a thermochemical process, and this process is known as pyrolysis. The waste biomass is heated at around 350-700 °C in furnaces built for extreme temperatures. This biomass contains rich carbon materials and is distributed to the affected areas of wildfires to enhance water retention in soil, increase nutrient storage capacity in soil, and increase carbon concentrations in the soil.

In practice, this method is carried out by trained teams who collect post‑firewood, leaves, and other organic debris and process them in specialized furnaces to produce biochar. This approach is increasingly used in wildfire‑prone regions such as California, British Columbia, and Oregon, where large volumes of burned biomass are available after major fires.

The resulting biochar is then blended with compost and applied to the soil at controlled rates, rather than simply being dumped in piles. When combined with mulch, wattles, and native seed mixes, these amendments help stabilize slopes, reduce erosion, and give seedlings a much better chance of establishing. Together, these practices speed up soil recovery, support vegetation regrowth, and enhance long‑term carbon capture in landscapes recovering from the effects of the wildfire.

Compost and ash reuse

After a wildfire, the ground is often covered with burned branches, leaves, and other debris. Instead of treating all this material as waste, many communities now turn it into compost or compost‑biochar blends and reuse it on the same land. In places like California, especially after major events such as the Camp Fire and the LA County fires, crews have used compost filter socks and similar products to stabilise slopes and protect waterways. These compost‑based tools help trap sediment, slow down runoff, and filter out contaminants from stormwater. By keeping this organic material in circulation rather than throwing it away, the process supports a more circular, sustainable approach to post‑fire recovery.

After a wildfire, the soil often becomes loose, water‑repellent, and extremely prone to washing away, so one of the first priorities is preventing erosion and landslides. To stabilise these fragile slopes, crews place compost‑based tools like filter socks and straw wattles across the burned hillsides. These materials slow down runoff, trap sediment, and stop ash and soil from being carried into nearby rivers and communities. By holding the ground in place during rainstorms, they protect water quality and reduce the risk of dangerous landslides while the landscape begins to recover.

Even though large‑scale composting is handled by trained crews, ordinary people still help keep the system circular. After a fire, residents can collect small amounts of clean organic debris—like leaves or branches—and send it to local composting programs instead of throwing it away. They can also support community compost hubs, join post‑fire clean‑ups, or simply sort their green waste properly so it doesn’t end up in landfills. In some places, homeowners reuse small amounts of clean wood ash in their gardens, or they plant native vegetation and spread community‑made compost to rebuild soil health. These small actions keep organic material circulating locally and, when many people take part, they help turn fire debris into something that protects soil and supports the landscape’s recovery.

Erosion control and nature‑based engineering

Erosion control and nature‑based engineering play a huge role in helping landscapes recover after wildfires, and they fit perfectly into a circular approach. Instead of relying only on heavy machinery or synthetic materials, these methods use natural elements—like logs, rocks, mulch, and native plants—to stabilise the soil and guide water safely across burned slopes. By working with the landscape rather than against it, these techniques help prevent the kind of severe erosion and sediment flows that often follow a fire. They also make use of materials already found on‑site, which keeps resources circulating locally instead of bringing in new ones.

Beyond protecting the soil, these nature‑based solutions create the right conditions for vegetation to return, which is essential for long‑term resilience. When native plants take root again, they hold the soil together, store moisture, and reduce the chances of future fires burning as intensely. Over time, the landscape becomes healthier and more stable, creating a natural cycle where the environment slowly rebuilds itself using its own resources. This is what makes erosion control and nature‑based engineering truly circular—they help the land recover in a way that strengthens it for the future, without generating waste or relying on outside inputs.

Even though most erosion‑control and nature‑based engineering work is done by specialists, ordinary people still have a meaningful role in keeping the whole system circular. After a fire, residents can help by clearing and sorting their green waste properly, supporting local composting programs, or joining community clean‑ups that collect safe organic debris for reuse. Homeowners can also plant native species, mulch their gardens, or use small amounts of clean wood ash to rebuild soil health. These simple actions might seem small, but together they keep natural materials circulating locally and help the landscape recover in a way that’s healthier, more resilient, and less vulnerable to future fires.

Case studies

Palisades fire, 2025

The Palisades Fire of 2025 was a heartbreaking moment for Los Angeles. It tore through the hillsides with terrifying speed, pushed by dry winds and months of drought, and left behind a trail of burned homes, damaged ecosystems, and families who suddenly had nothing.

But once the flames were out, something remarkable happened. Neighbours, volunteers, and local groups stepped in long before the official crews could reach every corner. People sorted their green waste properly, donated clean organic debris to composting programs, and helped lay down mulch and native plants to stabilise the soil. Community hubs organised clean-ups, checked on vulnerable residents, and ensured families had the basics they needed to get back on their feet. These small, steady acts—reusing safe materials, restoring soil, planting for regrowth—became part of a circular recovery that helped the land heal and reminded everyone that rebuilding isn’t just about structures, but about people showing up for one another.

Black summer, 2020

During Black Summer in Australia, everyday people played a huge part in helping their communities recover. While firefighters and emergency crews handled the frontline, residents supported the recovery in practical ways: clearing safe debris, sorting green waste properly, helping neighbors protect their properties, and joining local groups to plant native species once the fires had passed. Volunteers delivered supplies, checked on vulnerable families, and helped rebuild small parts of the landscape using simple, nature‑based methods. These steady, hands‑on actions didn’t just support the environment — they helped communities stay connected and move forward together after such a difficult season.

Russian wildfires, 2010

The Black Summer fires didn’t just hit southern Australia — Queensland, including areas not far from Brisbane, faced one of its toughest fire seasons on record. Between August 2019 and January 2020, more than 7.7 million hectares burned across the state, with major fires in places like Sarabah, Peregian Springs, and Stanthorpe. These fires destroyed homes, damaged ecosystems, and left hillsides vulnerable to erosion. But once the flames passed, communities stepped in with practical, circular‑economy actions. Residents sorted green waste properly so it could be turned into compost instead of going to landfill, volunteers helped clear safe organic debris for reuse in erosion‑control projects, and local groups planted native species to stabilise soil naturally. By keeping organic materials circulating locally — rather than treating everything as waste — people helped the land recover faster and reduced the risk of future fires. It became a quiet but powerful example of how everyday actions can support a more circular, resilient recovery.

Portugal wildfire, 2017

In October 2017, wildfires were amongst the worst in Portugal’s modern history. According to the European Commission’s Joint research centre about 296,613 hectares of land was burned across the centre of Portugal and supporting casualties of 51 death toll. Most eucalyptus and pine trees were destroyed as well as small rural villages. communities in Portugal didn’t just rebuild — they rebuilt differently. Instead of treating the burned landscape as waste, local groups leaned into circular, regenerative practices that worked with the land rather than against it. Burned logs were salvaged and turned into natural erosion‑control structures, laid across slopes as contour barriers, stabilizers, and small check dams that kept soil in place while the hillsides healed. In several regions, teams collected fire‑damaged eucalyptus and pine and transformed them into biochar, a carbon‑rich material that was mixed into depleted soils to boost water retention, improve nutrient cycling, and support the return of native plants.

Residents played a hands‑on role too — gathering native seeds, restoring old terraces, and helping re‑establish ecological corridors using traditional agroforestry knowledge. Even the smallest materials were kept in circulation: branches, leaves, and bark were reused as mulch and organic cover, protecting bare soil and feeding community composting efforts. Together, these actions turned a devastated landscape into a living example of how circular thinking can guide recovery, resilience, and renewal.

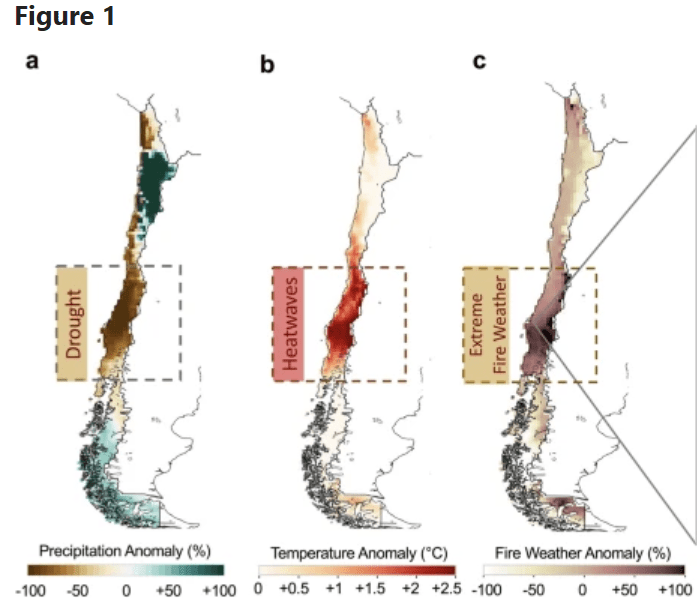

Chile wildfire, 2017 – 2023

The Chile wildfire was a different one as it started a new regime of faster, larger and more destructive and burned hectares of land within days. Year season in a year the fires would exceed more than 450,000 hectares giving it an all-time high in historical records and called it mega-fires.

Instead of treating the burned landscape as something to clear and discard, people across regions like Valparaíso, Maule, and Biobío turned toward circular, regenerative recovery. Burned branches and fallen timber were salvaged and used as natural erosion‑control structures on steep slopes, helping slow runoff and protect fragile soils. Local groups and forestry cooperatives collected fire‑damaged biomass and transformed it into compost and biochar blends, which were then spread across degraded soils to restore moisture, rebuild nutrients, and support the return of native species.

Community nurseries and seed banks — many run by volunteers — gathered seeds from surviving plants and grew thousands of native seedlings to replant burned hillsides, revive wildlife habitat, and reconnect ecological corridors. Even small organic debris like leaves and bark, was reused as mulch to shield bare soil and reduce erosion during winter rains. Together, these circular practices helped Chile rebuild not just its forests, but its sense of resilience — turning fire‑scarred landscapes into living examples of how communities can regenerate the land by keeping natural materials in circulation and working with nature rather than against it.

Conclusion: From ashes to growth

In the end, whether it was the Palisades Fire in 2025 or Australia’s Black Summer, one thing stayed constant: recovery didn’t rely on big systems alone. It grew from the steady, practical actions of ordinary people who chose to reuse what they could, support nature‑based solutions, and help their landscapes heal instead of starting from scratch. By keeping organic materials in circulation, restoring soil with compost and native plants, and working with the land rather than against it, communities showed that circular recovery isn’t just an environmental idea — it’s a way of rebuilding that strengthens people, ecosystems, and resilience all at once. These fires were devastating, but the response that followed proved that when communities act together, recovery becomes not just possible, but regenerative.