Urban mining has become a critical strategy as the world confronts growing scarcity of rare earth elements (REE) and other essential resources such as copper, lithium, cobalt, and precious metals. These shortages threaten clean energy transitions, digital infrastructure, and advanced manufacturing. Recovering valuable materials from e‑waste and discarded infrastructure is not simply a circular economy ideal; it is a practical response to one of today’s most pressing supply chain risks and a pathway to resilience across multiple industries.

Legacy of mining

Traditional mining has a long history, starting from the Egyptian and Roman times for extracting metals such as gold, copper, and silver. Mining has been passed down through generations and has become an integral part of modern civilization, enabling the resources that make transportation, electronic devices, everyday objects, and even currency possible.

Modern mining issue

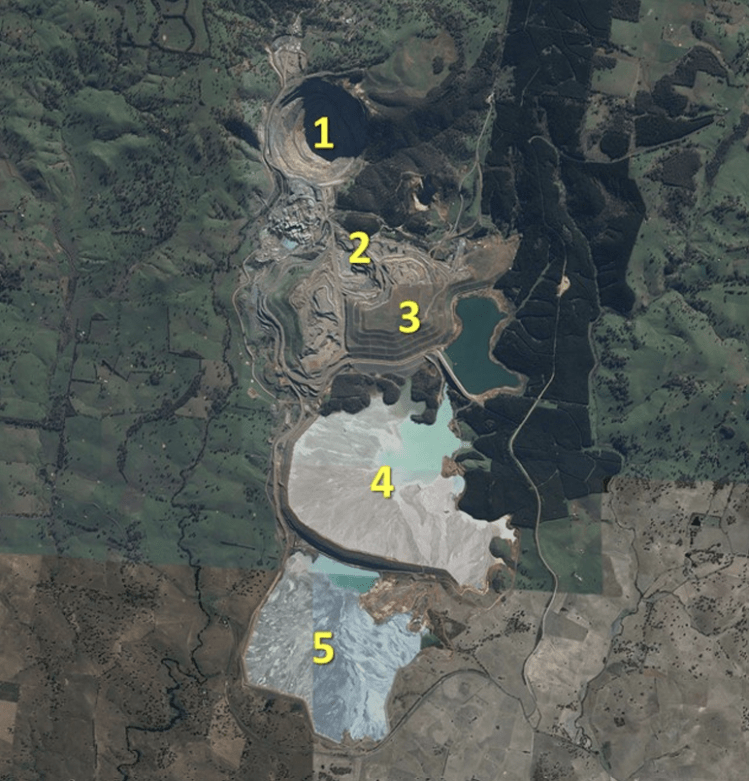

In recent times, the pace of metal extraction has accelerated far beyond nature’s ability to replenish or concentrate these resources at the Earth’s surface. The result is vast environmental damage: open‑pit mines that leave scars visible from satellites, wounds that may take centuries to heal. Mining operations now span every continent, targeting everything from iron ore to rare earth elements. These sites are tightly woven into the global supply chain, feeding the urgent demand for materials that power modern life — smartphones, vehicles, and defense technologies. Yet this urgency comes at a dangerous cost. For example, producing just one ton of rare earth elements can generate up to 1,850 tons of waste material and release toxic byproducts into soil and water. Such figures underscore the imbalance between our technological ambitions and the planet’s ecological limits.

Urban mining: A Circular Alternative

Urban mining offers a sustainable path forward. Instead of digging deeper into the Earth, it turns to the waste streams of cities — discarded electronics, appliances, and devices rich in rare metals. By recovering and repurposing these materials, urban mining reduces reliance on destructive extraction, closes resource loops, and transforms cities into reservoirs of valuable resources. With the volume of e‑waste produced globally, urban mining has the potential to meet significant demand while aligning with circular economy principles.

The hidden costs of traditional mining

Environmental scars

For miners to be able to mine precious or common substances, huge craters are dug into the Earth, which are several kilometres wide and go very deep. This essentially destroys the several layers of healthy soil, and these layers are hard to get back and take lots of years to be restored, resulting in the lack of trees growing compared to the rate of cutting down trees for mining. The heavy amount of soil erosion can also increase the possibility of landslides due to loose gravel, which is often dangerous for humans and animals in the region.

On the other hand, mining produces lots of pollution containing dangerous substances such as sulfur and leaks from sulfides, and having contact with air can create acidic runoff, which can contaminate nearby groundwater or rivers flowing into important biodiverse regions. The pollution leaking into the air also worsens the air quality in general and can impact surrounding animals and plants by developing respiratory diseases and issues. The release of heavy metals through acid leakage and pollution can also affect the soil biodiversity and strength, as metals such as arsenic, mercury are highly dangerous.

Across the world, abandoned mines number in the millions, leaving behind more than empty pits. Untreated sites continue to release toxins into soil and water, turning surrounding areas into lifeless wastelands where plants cannot grow, and animals cannot survive. Heavy metals and acidic drainage seep for generations, poisoning ecosystems long after mining stops. Beyond local devastation, the industry’s carbon emissions add to global warming, making abandoned mines not just scars on the land, but enduring sources of pollution and climate harm.

Waste paradox

For a small piece of usable metal, lots of waste is extracted and wasted, thus creating a bigger waste pile than the amount actually used. This means that for a small yield, more earth is displaced with serious damage, which is especially true for rare and precious metals.

Mining generates several forms of waste, including waste rock, tailings, and poisonous water. Waste rock is typically dumped in large heaps near mining sites, but if it contains sulphides, these can seep into the soil and contaminate surrounding ecosystems. In some cases, rocks and sediments are backfilled into the mine after extraction to prevent ground collapse and reduce surface damage.

Tailings, a fine slurry filled with toxic materials, are usually stored in dams or tailing ponds. While these structures are designed to contain waste, failures and spills can have catastrophic consequences for nearby communities and environments. Treating tailings through specialized processes is possible, but the costs are extremely high, meaning it is rarely implemented on a large scale.

These issues create a paradox of waste in traditional mining operations, a cycle of destruction that produces more waste than usable material.

Social impacts

Mining consumes vast areas of land, often forcing nearby communities to relocate. The burden falls disproportionately on those with fewer resources, as wealthier cities and affluent neighborhoods are rarely affected. Instead, it is indigenous tribes, lower‑income families, and marginalized groups who face the greatest disruption — losing homes, cultural ties, and livelihoods to make way for extraction.

For many local communities, mining becomes the only available source of livelihood. Yet this dependence is often exploited: companies pay unfair wages, cut corners on safety, and provide inadequate protective gear. Vulnerable populations shoulder the dangers of toxic exposure and hazardous conditions, while corporations profit from reduced costs, putting human rights into question.

An even darker reality is child labor. Families struggling to survive are forced to send children into mines, where they are easier to exploit and manipulate. What begins as a fight for income becomes a cycle of exploitation, stripping communities of dignity, health, and opportunity.

As mining expands, the very foundations of local livelihoods begin to collapse. Farming, fishing, and hunting — once reliable sources of sustenance — are disrupted as biodiversity declines and ecosystems unravel. Access to clean water becomes scarce, with pollution from mining operations seeping into rivers and wells. The outcome is devastating; communities are left to starve, forced to rely on contaminated water, and exposed to long‑term health risks such as respiratory illnesses and cancers. What remains is not prosperity, but a cycle of loss and suffering.

Rare Earth metal scarcity

The digital age has become more prevalent in modern-day civilization, from using electronic devices to speak to loved ones to using AI as a friend. At the heart of this technological revolution lie REEs such as neodymium, dysprosium, and terbium. These metals are indispensable: they drive the magnets in electric vehicle batteries, power the turbines that capture clean wind energy, and enable the smartphones that connect our world.

As rare earth metals become the new oil of the digital age, urban mining emerges as a circular solution that transforms waste into resilience. These rare metals are immensely needed for providing clean energy, semiconductors, and other manufacturing areas, which is why these metals have more demand than other metals.

Urban mining as a circular solution

Recycle and reuse

In urban mining, the destructive waste paradox of traditional mining simply does not occur. By taking a circular approach, discarded e‑waste becomes a valuable resource. Electronics such as smartphones and laptops often contain higher concentrations of precious metals than natural ores, and their recovery produces far less waste. Unlike traditional mining, which generates mountains of waste rock, urban mining extracts metals directly from existing products, eliminating the need to scar the land.

Urban mining also ensures cleaner processing. Modern segregation facilities use controlled temperatures to separate and recover maximum amounts of valuable metals while releasing minimal waste. This streamlined process produces significantly lower carbon emissions compared to traditional mining, which drags on for months and leaves behind vast amounts of toxic residue. Operating within a closed‑loop system, urban mining is safer, more environmentally friendly, and far more energy‑efficient — turning society’s waste into a sustainable source of wealth.

Geopolitical

Rare earth elements are heavily concentrated in a handful of countries, with China alone controlling around 60–70% of global mining and nearly all refining capacity. This dominance means politics and geography often prevent unified international action to measure mining waste or expand sustainable solutions. Trade restrictions and geopolitical tensions further limit cooperation, creating fragile supply chains vulnerable to shortages and price shocks. The consequences fall hardest on lower‑income communities, which face rising costs and reduced access to technologies essential for education, energy, and livelihoods.

Urban mining offers a circular solution with profound geopolitical implications. By recovering metals from discarded electronics — which often contain concentrations far higher than mined ores — urban mining reduces dependence on destructive extraction and mitigates the risks of geopolitical choke points. With global e‑waste projected to exceed 74 billion kilograms annually by 2030, the potential for recovery is enormous. Urban mining would decentralize the mining pattern, encouraging waste to be collected and repurposed locally in cities worldwide, reducing dependence on imports from countries like China, Brazil, and India.

Supply chain resilience

Similar to geopolitical stress reduction, the amounts of imported goods would also reduce and encourage repurposing local industrial waste, thus trade restrictions do not apply like export bans. As the World Economic Forum (2023) notes, urban mining can decentralize resource recovery, reducing reliance on concentrated supply chains in countries like China, and improving resilience against geopolitical shocks. This also ensures are stable supply chain for the local cities or towns as there would be a steady flow of recovered material from existing waste, keeping the waste industries running while also ensuring people have access to clean energy, and get local independence.

Economic opportunity

Urban mining doesn’t just create a circular system — it also unlocks new pathways for economic growth and social inclusion. By ensuring a steady flow of recovered metals, it stabilizes supply chains and keeps industries running. But beyond that, it generates local jobs and opportunities, especially for individuals from lower‑income backgrounds.

Accessible skill sets: Urban mining aligns with economic development standards because it creates entry‑level, practical jobs that are accessible to a wide range of workers. Recycling and repurposing require practical skills — sorting, dismantling, and processing. With less than 20% of e‑waste currently recycled, the opportunity for job creation and community resilience is immense.

Community‑based industries: Urban mining facilities can be established in cities where waste is abundant, creating local employment hubs and reducing dependence on distant mines, and providing an opportunity for including this in education.

Revenue production: Extracted metals from electronic devices such as smartphones can contain valuable metals like gold, copper, and RREs. A single smartphone contains 7 to 34 milligrams of gold, which equates to $0.60 and $2.50. When collected in bulk, the value of recovered metals becomes enormous. For example, one million smartphones can yield up to 30 kilograms of gold, alongside hundreds of kilograms of silver, copper, palladium, and rare earth elements. This translates into millions of dollars in recoverable value from devices that would otherwise end up in landfills. Urban mining would drastically increase a region’s revenue with all the salvaged metals from waste products.

Urban mining creates an economic opportunity for everyone who is focused on sustainability in terms of the environment and the local community. With sustainability being an essential part of a local system, urban mining ensures that economic growth, resource recovery, and social well‑being move hand in hand, building a future that is both resilient and inclusive.

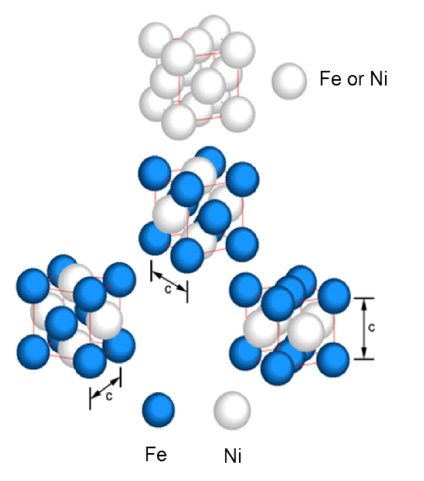

Innovation to reduce reliance on REEs

Beyond urban mining, scientists are exploring extraordinary alternatives like Tetrataenite — a meteorite alloy with magnetic properties similar to rare earths. While it is rare and difficult to replicate, research into such space materials shows how innovation and circularity together can reshape our resource future.

Tetrataenite is a metal alloy found in meteorites, which has been found to work as well as rare earth metals, helping with magnetism, semiconductors, and providing clean energy. For years, scientists have been searching for a material that can substitute for rare earth metals and have found Tetrataenite. They are now trying to replicate its properties in labs to create an endless supply of magnetism for manufacturing high-tech devices. However, this material cannot be found on Earth, thus making it extremely limited for use and hard to replicate.

Even if it is not available in plenty, at least 17,000 meteorites fall on Earth every year, which allows scientists to research more with different materials and find out solutions to produce clean energy from space material. Even if Tetrataenite itself remains scarce, the effort to replicate its properties in laboratories highlights a broader principle: innovation can complement circularity by expanding the range of sustainable materials available to society.

Conclusion

Mining has long sustained human progress, but its legacy of waste, displacement, and ecological harm now overshadows its benefits. Communities lose homes, livelihoods, and health, while landscapes bear scars that may never heal. Yet within this crisis lies opportunity: urban mining offers a circular alternative that transforms discarded electronics into valuable resources, reducing dependence on destructive extraction. By decentralizing recovery, it strengthens supply chains, creates local jobs, and lowers emissions. Innovation, from advanced recycling to research into substitutes like tetrataenite, expands the horizon of possibilities. Choosing circular solutions means building resilience, equity, and sustainability into our future — turning society’s waste into wealth and ensuring prosperity without sacrificing the planet that sustains us.