Slums, home to over 1 billion people worldwide, are the frontline of urban vulnerability. Overcrowding, poor sanitation, unsafe housing, and climate change converge to create daily risks of disease, displacement, and poverty. Open sewage contaminates water, fragile dwellings collapse under floods, and limited healthcare magnifies crises. Yet within these challenges lies opportunity: by inducting circular practices—such as waste-to-energy digesters, repurposed construction materials, and community recycling hubs—slums can transform hazards into resources. Circular solutions not only reduce illness and environmental damage but also generate livelihoods, strengthen resilience, and pave a way forward toward healthier, more sustainable urban futures.

What are slums?

Slums are informal settlements that typically arise in urban areas, often outside the bounds of formal law. In rapidly expanding cities such as Mumbai, Nairobi, and Manila, relentless population growth and overcrowding create stark economic imbalances. With formal housing priced far beyond reach, many residents are compelled to construct makeshift dwellings from whatever materials they can access. These homes, lacking durable construction, plumbing, transportation, and electricity, expose communities to unsafe living conditions. The result is a cycle of poor sanitation, inadequate hygiene, overcrowding, and insecure tenure, where vulnerability becomes a daily reality.

Effects of slums on people and the environment

Social and health impact

Hygiene and water – Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) are important to public health. Slums are known to lack proper facilities such as toilets, untreated water, and proper plumbing. Often in these circumstances, individuals have to use shared facilities that are contaminated due to very little or no maintenance. This can lead to outbreaks of diseases such as cholera and frequent cases of diarrhea, as fecal matter in water can lead to bacterial growth and eventually water-borne diseases. The overcrowded regions can suffer from tuberculosis outbreaks due to closeness and other respiratory diseases, thereby impacting a majority of individuals.

Open sewage – Sewage is usually built through a network of pipes and is engineered to keep the flow of water running and not flow backwards at any point, as even slight movement in water can encourage bacterial growth. These systems are not incorporated in slums, and people often rely on community toilets or drains, which increases the bacterial growth in the sewage. Stagnant sewage can attract insects such as mosquitoes, which are known for spreading malaria. Individuals resorting to drinking or using the water are prone to sexually transmitted diseases, respiratory diseases, and other dangerous health defects.

Climate change – In the present day, climate change is a contributing factor to the human population and especially in crowded regions. Climate change manifests through intensified flooding, heat waves, and water scarcity, all of which disproportionately affect slum residents. With homes often built from weak or recycled materials, heavy rains and rising sea levels can destroy shelters and contaminate drinking water, leading to outbreaks of diseases. Extreme heat worsens health risks in densely packed areas where ventilation is poor, while droughts and erratic rainfall reduce access to clean water and food. Because slum communities typically lack formal drainage, sewage, and healthcare systems, they cannot buffer against these shocks.

Environmental impact

Open sewages in slums often end by flowing into rivers untreated. Rivers and groundwater are used for drinking water in most urban areas in the world. The pollution of rivers and groundwater can hamper the health of not only slum dwellers but also urban and rural areas. Marine health gets compromised with coastal marine life being affected by different sorts of diseases or dying in the process. These nutrients in the sewage can lead to excess algal growth in rivers or lakes and disrupt sunlight from reaching underwater, thus endangering respiration and photosynthesis for marine species. Marine species are also in the process of being affected by habitat destruction, reduced oxygen, and toxic pollutants.

Farm regions are also vulnerable, as soil fertility can be reduced with disease-infested sewage water. This would essentially harm lots of farm insects and organisms that depend on the farm for food and shelter. Last but not least, the populations residing in urban areas would be affected most, as food and water are a vital necessity for people. And with an increasing population, the need for farmland is even more sought after than ever.

Beyond the slums themselves, these conditions spill over into wider urban systems, raising healthcare costs, reducing productivity, and deterring investment. Once groundwater is polluted, it is very difficult and expensive to restore it with purification systems, which is a huge problem in countries that are less financially stable. In this way, inadequate sanitation perpetuates cycles of poverty and inequality, draining resources that could otherwise fuel sustainable development.

Economic impact

Due to the risk of hygiene, sanitation, and water being worse in slums, the inhabitants of slums are usually mostly too weak for helping in community practices or taking care of themselves thus quality and conditions of the little facilities they do have and endangering the mortality rate of the younger generation. This forces families to spend more on medical treatment and transport as proper medical facilities aren’t found nearby. Families and individuals tapped into medical debt cannot escape poverty, thus increasing their longevity of living there and increasing the rise in population in the long term.

The economy is dependent on the younger generation to thrive; however, it is hard to see them thrive in slums, as a weaker public community decreases the chances of community building, such as hospitals, schools, and other facilities important for a thriving population. This essentially weakens the informal economy that the residents have built in the slum. Child mortality and poor health, increasing in the long term, can lead to less overall productivity with young, healthy citizens and less building of proper facilities and maintenance.

Circular solutions for slums

Waste management and sewage

Smart NGOs and funded organisations motivated to help slums are helping manage the sewage entering rivers by organizing community-led recycling operations. Citizens will be paid for retrieving polluting materials such as plastic bags, cans, and other materials, and giving them to the particular organisation for recycling. NGOs are also committed to educating the citizens of slums on composting or organic waste to grow their own medicinal plants and solutions to beat health sicknesses.

Case Study – Siddharth Nagar

One such organization, Earth5R, has made remarkable efforts to uplift the lives of residents in the slums of Siddharth Nagar, Mumbai, by working hand in hand with local partners. In this densely populated settlement, overflowing bins, garbage fires, and blocked drains had long plagued daily life. To address these challenges, Earth5R introduced the philosophy of Respect, Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, and Restore, empowering communities with practical solutions. Residents were educated on waste segregation and incentivized to collect recyclable materials from landfills, transforming waste into valuable resources. Beyond waste management, civilians were also encouraged to cultivate medicinal plants and herbs, fostering self-reliance and improving nutrition for everyday consumption. Together, these initiatives not only reduced environmental hazards but also nurtured healthier, more resilient communities.

Energy solutions

As biological waste in slums is one of the reasons for illnesses to reduce this by implementing machines such as digesters is important. Digesters are vessels created to turn waste into methane, which acts as biofuel. Building toilets with plumbing connected to these digesters can possibly turn lots of human waste and food scraps into clean cooking gas, which reduces the need for deforestation or the use of kerosene. 300 liters of biogas are enough to feed one person’s meal. With slums harbouring a big population of humans, their daily contributions to the digester can create tens of cubic meters of biogas per day, ensuring clean food and less disease transmission.

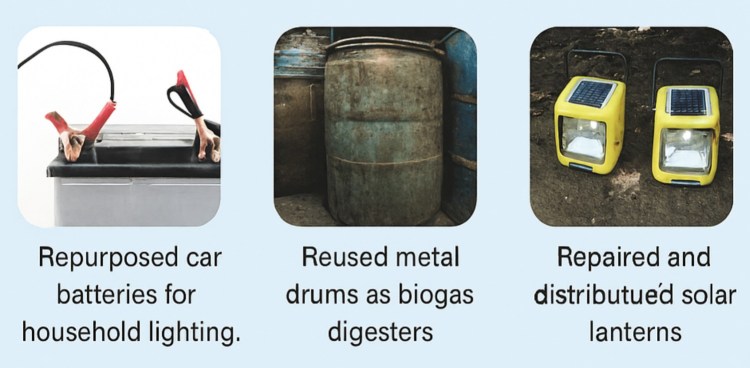

With consumerism on the rise, the production and reselling of energy devices are in abundance. People can make sure to resell energy devices they own that are not working properly to repurposing areas that provide energy to slums. These energy devices can be repurposed and upcycled from car batteries to house lighting, metal drums to biogas, and repaired solar lanterns remade from spare parts. This would significantly improve the lives of slum inhabitants by improving their safety, satisfaction, and many other daily life issues.

Case study: Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro’s favelas house millions of people in informal settlements and slums where energy access is limited. Traditional grid access was limited to the inhabitants of the favelas and relied on unsafe methods of using electricity. The Revolusolar NGO, along with other partners, developed a system that prioritized community-run initiatives utilizing solar power from solar panels installed on the rooftops of houses in community centers and housing blocks of the slums. These panels were regularly maintained, enhancing their longevity and circularity. Food and organic materials were also fed into localised biogas digesters to create gas for cooking and electricity generation as well. These motives were enhanced with community residents taking action together to manage these energy systems, and revenues made from the energy saved were incorporated into education and health departments.

Construction materials

The urban cities are developing every day with more people wanting to move to cities due to jobs and way of life. With lots of construction materials being put to waste and put into landfills, these materials can be repurposed in slums. A zero-waste economy would be one where repurposing materials, especially building materials in slums, would be very useful, as it would improve living conditions drastically. People enjoy their own safe space to feel safe, and to do that, initiatives such as the “Learn to Earn” are an increasing practice in slums. This program aims to educate civilians to learn how to deal with recycled and repurposed construction materials. Materials such as wood, bricks, and concrete rubble are cheap and can be used for housing upgrades and community facilities. With slums receiving less help from outside services, this method builds independence in their own living conditions while also generating their own income. Using the zero-waste economy concept, slums can be a model example to be looked at by other urban city dwellers.

Case Study: Cape Town

Slums in Cape Town are slowly implementing their practicing into more circular zero-waste economy strategies. Companies such as The Real Deal 2 Cheap are purchasing construction and demolition waste and employing slum inhabitants to sort and repurpose the materials and incorporate them in the slums these people live in. These materials are eventually repurposed waste wood into door frames, roof tiles into kitchen sinks, and more.

How these solutions have helped

Beyond their technical promise, circular solutions have already demonstrated tangible health benefits across slum communities worldwide. The issue of open sewage and hygiene concerns, along with circular solutions like waste-to-energy, has helped mitigate health risks on a global scale. In Nairobi, up to 30% of children suffered less from diarrheal diseases due to the introduction of biogas from digesters, and also indirectly reducing respiratory diseases.

As mentioned above, repurposing and recycling materials have become a significant part of circular solutions, providing income opportunities to slum dwellers and ultimately increasing their economic empowerment. With opportunities such as waste pickers and recycling hub workers have become an integral part of cities and their economy.

The repurposing of construction materials has also assisted the people in slums to defend themselves against climate change and build their resilience. With stronger and better infrastructure, houses can withstand floods and storms. The implementation of solar grids on houses has also lessened slum dwellers’ dependence on unsafe grid connections and significantly benefits the environment.

All of these advancements have been possible because of strong community presence—at the heart of what circular initiatives represent. By fostering collaboration and building their own systems of local governance, residents benefit from better decision‑making and are no longer solely dependent on outside aid. In Jakarta, Indonesia, slums have formed their own local committee and have addressed different issues such as allocating and managing resources, coordinating with the Indonesian government, and negotiating relocation for better resources. This collective empowerment not only enhances resilience but also serves as an inspiring model for other communities seeking sustainable transformation.

Conclusion

Slums represent some of the most urgent challenges of urban growth, yet they also hold untapped potential for transformation. By adopting circular practices—such as biogas digesters, recycling hubs, repurposed construction materials, and renewable energy cooperatives—communities can turn daily hazards into opportunities. The case studies from Mumbai, Rio de Janeiro, and Cape Town show that when residents, NGOs, and local partners collaborate, informal settlements can evolve into resilient, self‑sustaining neighborhoods. Rather than being defined solely by vulnerability, slums can become living laboratories of innovation, charting a path toward healthier, more equitable, and sustainable urban futures.