Nitrogen is a very important nutrient to help plants grow, as it is a major component in chlorophyll, which plants use to photosynthesise. Thus, nitrogen builds more yield for most plant species, compelling farmers to use it for better produce. The agricultural community uses fertilizers and manure, which carry huge amounts of different types of nitrates to increase plant yield, replenish soil nutrients, enhance soil stability, and much more. However, with nearly half of the world’s food production relying on fertilizers, it raises important questions about the impact of nitrates on coastal waters. Nitrates from farmed water commonly run off into lakes, estuaries, and groundwater, which affects overall coastal marine health. Let’s discover what issues arise due to this and what can be done to mitigate them.

Geographic drivers of nitrate runoff

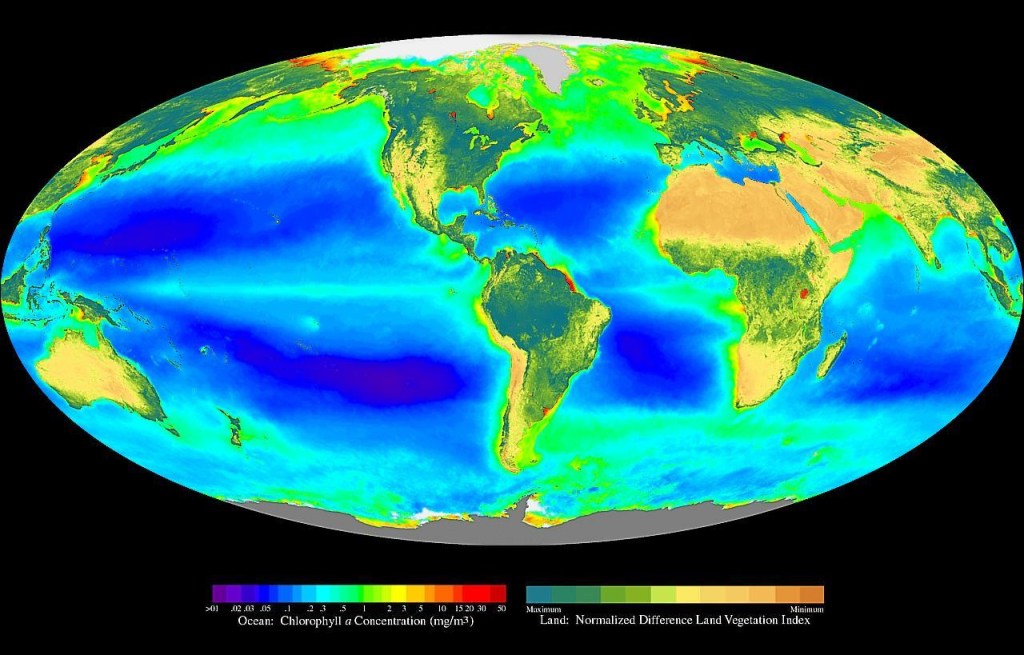

Coastal waters, especially in regions closer to the poles, tend to be more biologically productive due to uniformly cold temperatures that promote year-round nutrient mixing. This constant circulation ensures that nutrients — including those from agricultural runoff — are evenly distributed throughout the water column, fueling rich ecosystems. However, when excess nitrates enter from nearby farmland, especially in polar or subpolar coastal zones, they are rapidly absorbed into the marine system. This amplifies the risk of eutrophication and ecological disruption, meaning that even small-scale runoff can have outsized impacts on marine biodiversity. Regions like the Gulf of Mexico and southern Peru have experienced extensive dead zones due to large-scale HABs and ongoing ocean acidification. These areas are among the most biologically productive seas, which makes them especially vulnerable to nutrient overload and ecological disruption.

Nitrates from fertilizers often mix with water and travel from farmland into surrounding ecosystems. In regions with sloped terrain, this runoff is especially pronounced, accelerating the movement of nutrients toward coastal zones. While nitrogen is essential for plant growth — both on land and underwater — excessive nitrate accumulation can disrupt delicate marine balances. Coastal waters, as noted by Britannica, support a significantly more diverse life force than the open ocean, making them particularly vulnerable to nutrient overload and pollution.

Problems arising from nitrate runoff

Eutrophication

Eutrophication is a broad term that encompasses a range of harmful processes triggered by various environmental imbalances. One of the key contributors is nitrate runoff from agricultural land, which often finds its way into coastal waters. This can set off a chain reaction that disrupts the natural balance of marine ecosystems.

Harmful Algal Bloom (HAB)

Algae blooms are a natural, recurring part of the life cycle; however, nitrates can provide a boost and break this pattern. This accumulation essentially increases the growth production of algae and plankton in the area. With a rapid growth in plant matter it can cover the sunlight, covering the surface water thus leading to plants underwater to die off due to lack of oxygen and sunlight for photosynthesis. Without oxygen from the surface for respiration fishes suffocate. This phenomenon is HAB and can happen anywhere and can harbour different species of algae however as of now farming is the leading cause making it an anthropogenic issue.

Acidification

Due to the algae bloom expanding rapidly, when all the plant and algae matter die off, carbon dioxide (CO2) is released. A study in 2025 revealed how algal blooms release more CO2 than usual, accompanied by methane. These are greenhouse gases and is causing the warming of the planet as we speak. The increase in CO2 and methane can increase the acidity of the atmosphere and ocean.

Fisheries and coral reef stress

Coral reefs are an integral part of the ecosystem, providing a diverse range of habitats for various species of fish and other organisms, and harbouring most fish that are consumed by humans through fishing.

Coral reefs rely on a symbiotic relationship with certain algae species that give them their color and provide essential nutrients. However, nitrate accumulation from agricultural runoff can destabilize this relationship, leading to coral bleaching and increased sensitivity to environmental stress. Reefs in eutrophic zones are particularly vulnerable, as excess nutrients fuel HABs and contribute to hypoxia — a condition of low oxygen. Scientists have identified hypoxia as a significant factor in coral bleaching. In the Caribbean, a major bleaching event was preceded by hypoxic conditions, which disrupted microbial communities and resulted in widespread coral mortality.

They support approximately 6 million fisheries in nearly 100 countries, underscoring their significance for global food security. Due to acidification, HABs, and resulting eutrophication, the decline in reef health is threatening the fish populations we rely on. This is especially impacting coastal communities that depend on seafood for their daily diets and livelihoods, as fish stocks dwindle and economic stability deteriorates, thus does not form a good circular economy.

Adapting farming practices to mitigate nitrate pollution

Precision farming

To ensure most nitrate from the farm is used in other areas and minimum nitrate is dumped into oceans in the form of runoff, more circular practices must be implemented. Precision farming is a form of farming where fertilizers are applied only where needed to minimize nitrate runoff. Precision farming also uses technologies such as airborne drones for mapping and artificial intelligence-integrated irrigation systems, reducing resource use and increasing energy efficiency.

Regenerative farming

Regenerative practices in different types of farming practices can be implemented. This a very impressive technique for establishing circular economy for several reasons. Cover cropping is one such technique where crops such as grass or legumes are grown which essentially strengthens the soil naturally and prevent erosion in offseason time when agricultural crops are not in demand grown. This ensures minimization of fertilizer use thus need less nitrates to ensure crop and soil stability. With better soil stability more nitrates in runoff water can be used up for other plants growth not in the farm area.

Civilian approach to regenerative farming

Civilians at home can contribute to regenerative farming by practicing food composting in their backyards or on a small scale. This approach effectively reduces food waste and, when supported through community initiatives, can be applied to soil to enhance its stability. Healthier, compost-enriched soil has a greater capacity to retain groundwater and absorb runoff containing nitrates, helping to prevent nutrient pollution and support local plant growth.

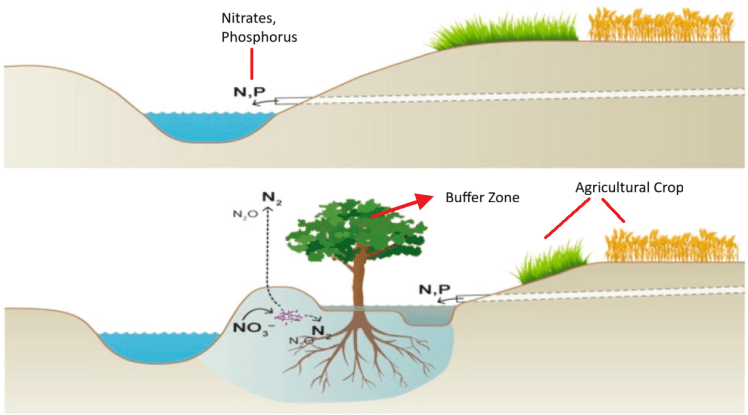

Implementing buffer zones

Buffer zones in this context would be shrubbery or trees and plants that are not part of farmed crops and are placed between planted agricultural crops and natural environments such as wetlands or streams. This allows nitrate runoff to get absorbed by the complex root structures in the soil for these plants. Essentially, it slows down the velocity of the runoff and reduces nitrate content in the runoff water, especially on slopy areas. This is a good circular approach as the soil is also enriched by these extra nutrients what the farm wastewater.

Buffer zones also play a vital ecological role by serving as habitat hubs for small creatures such as worms, butterflies, pollinator insects, and natural predators. These vegetated strips function as ecological corridors, supporting biodiversity and enabling the movement and survival of various species — including those that are threatened. Pollinators like bees and butterflies contribute to crop fertilization, while decomposers such as ants and worms assist in breaking down organic matter, including dead crops, enhancing soil health. By fostering these beneficial organisms, buffer zones strengthen ecosystem services that support both agricultural productivity and environmental resilience.

Mangrove restoration for coastal resilience

Coastal waters are among the most affected regions by nitrate runoff, largely because many major cities are built near oceans and other waterbodies. In regions such as the Middle East, Mediterranean, and South Asia, mangroves naturally thrive in salty wetland environments. These incredibly resilient plants have evolved to filter nutrients and survive in waterlogged, muddy coastal conditions. Mangrove ecosystems slow down water flow and trap excess nutrients like nitrates, functioning much like enriched soil in their ability to filter and stabilize. Over time, mangroves can regenerate degraded coastal areas across vast distances, highlighting their ecological significance. Although mangrove systems take years to fully develop, their long-term benefits — including nutrient recycling, shoreline protection, and biodiversity support — make them a cornerstone of circular economy strategies in coastal restoration.

Civilian approach to circular mangrove restoration

Planting mangrove seeds is a relatively simple task when done under the right conditions. Through community service and citizen science initiatives, people can volunteer to plant seeds, monitor mangrove development through regular assessments, and use technologies such as remote-controlled drones equipped with sensors to track pH, temperature, soil salinity, and texture. Volunteers may also assist in collecting soil samples for scientific analysis. Mangrove parks that charge a small fee for citizen science participation and recreational access can generate funding to support ongoing restoration efforts — reinforcing a circular economy where public engagement, ecological regeneration, and sustainable financing are interconnected.

Initiatives like Emirates Nature–WWF in the UAE are prime examples of citizen science driving forward nature-based solutions. Through public engagement in mangrove restoration, volunteers help monitor tree health, track biodiversity, and collect data on water quality — all of which inform adaptive management. This hands-on participation not only reduces project costs but also attracts funding and community investment. By involving citizens in the stewardship of coastal ecosystems, these programs reinforce circular principles: nutrients are cycled, waste is minimized, and ecosystems regenerate.

Palawan case study

The coastal regions of Palawan, in the Philippines, are always facing heavy mangrove degradation due to coastal farming such as seaweed farming, aquaculture, and coastal development, which produce significant nitrate runoff into nearby waters. Mangroves were strategically planted near aquaculture and agricultural zones to intercept this runoff. The community-led restoration led to long-term soil stabilization, improved water quality, and influenced policies to sustain these gains. Scientific monitoring and policy engagement ensured the efforts were both ecologically effective and socially inclusive. This model shows how circular economy principles can regenerate ecosystems and empower communities as stewards of coastal resilience. Initiatives like this always take place in these coastal areas and are quite common, showing great community integration.

Individual action through environmental policy support

While large-scale change often starts with government action, individuals can play a role by abiding to local environmental policies and supporting initiatives that reduce nitrate pollution. This includes following guidelines on fertilizer use, respecting protected buffer zones near farms and waterways, and participating in community composting or restoration programs. By staying informed and choosing eco-friendly practices, people help reinforce the goals of these policies — creating a ripple effect that strengthens circular ecosystems from the ground up.

Chesapeake Bay case study

The Chesapeake Bay, the largest estuary in the U.S., faced severe nitrate pollution from intensive farming and over a hundred nearby factories discharging nutrient-rich waste. In response, the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement required all factories by 2005 to obtain permits limiting waste output. This policy shift encouraged farmers to adopt regenerative practices and communities to engage in composting and citizen science. By 2024, nitrogen loads had dropped by 4.1 million pounds — a notable improvement over the usual 3-million-pound annual reduction. These efforts reflect a successful circular approach, where policy, public action, and ecological restoration work together to regenerate coastal ecosystems.

Conclusion

Nitrate pollution in coastal waters is a growing global concern, driven largely by unsustainable farming practices, industrial discharge, and poor land-water management. Its consequences — from harmful algal blooms to declining fisheries — threaten both ecological balance and human livelihoods. Yet, the path forward is clear. Solutions rooted in circular thinking, such as precision and regenerative farming, can reduce runoff at the source, while buffer zones and nature-based restoration intercept before they reach the sea. Civilian efforts — from backyard composting to citizen science — amplify impact, proving that everyday actions matter. Embracing smarter land use, supporting restoration, and aligning with environmental policies, communities worldwide can help transform pollution into regeneration and resilience.

2 thoughts on “How farm Nitrates pollute coastal waters? What we can do to stop it?”