The Indian Ocean covers more than 70 million square kilometers per area. It is home to millions of diverse species and valuable minerals that humans rely on for livelihoods, food security, and transportation. The Indian Ocean is known for housing most fisheries on Earth due to its productivity, producing 14% of all global fisheries according to the Food and Agriculture Organization. It supports millions of livelihoods through fishing, trade, and tourism. However, rising threats like overfishing, species loss, and unregulated practices demand a shift from the traditional use and throw to a circular economy — one that regenerates ecosystems, reduces waste, and sustains communities.

Circular Economy in Fisheries

A circular economy is all about minimizing waste and maximizing resource output by allowing natural growth to flourish. The fisheries in the Indian Ocean are responsible for 30% of the assessed stocks, which are fished unsustainably. This has turned heads to look for more sustainable options to be able to feed a huge population.

Current circular economy practices in the Indian Ocean fisheries include Gear Recycling and Waste Management, Integrated Aquaculture Systems, and Fish Waste Utilization. All these practices ensure that waste such as fish byproducts is recycled and organisms in the same taxa are given for nutrient recycling. Gear Recycling and Waste Management is the most practiced as it ensures the recycling of fishing nets, as it is the number one polluter, which is harder to decompose.

While the circular economy in the marine industry in general makes an important step to sustainability, it is still important to understand the role the Indian Ocean plays in acting as a cornerstone for global fisheries. Understanding its scale and significance helps frame why circular economy intervention is so critical in this particular region.

Role of the Indian Ocean in Global Fisheries

The Indian Ocean plays a vital role globally; millions of people depend on it for food and nutrition. Around 800 million people living in the Indian Ocean region depend on its nutrition, including calcium, iron, and other essential vitamins. With 30% of calcium is exported globally from the Indian Ocean shows the vast amount of biodiversity it holds.

The Indian Ocean supports the commercial fishing of important species such as tuna, sardines, and other reef fishes. Throughout the years, its productivity has increased thus unlike the Atlantic and Pacific, the Indian Ocean’s fishing productivity has increased since the 1950s. Small-scale local fisheries have gained 300% productivity, making the Indian Ocean a critical hub for both global seafood supply and regional food security.

Yet, there is a cause for concern as demand rises, the fish stocks in the Indian Ocean are fished frequently and unsustainably. Nowadays, the dominance of export fishing is being favored more, leaving limited access to fish stocks for local communities. This practice is threatening long-term viability in the Indian Ocean as economic gain is prioritized over ecological sustainability.

Alarming Case Studies from Indian Ocean

Species Disappearance

As fishing increases in the Indian Ocean, certain causes for concern are rising. A science paper focuses on how, in recent times, the disappearances of big fish such as Humphead parrotfish and Bull sharks are now critically depleted in the western part of the Indian Ocean. These species, usually originating from coral reefs, have vital functions in the community such as predatory work, grazing, and maintaining a balance in the ecosystem.

Unregulated Fishing

Recently, a report published by WWF and Trygg Mat Tracking (TMT) highlighted how unregulated fishing was taking place in the Indian Ocean, where no laws or legal requirements were followed to fish in some regions of the ocean. According to the United Nations, the Indian Ocean faces an overwhelmingly smaller amount of regulation than the Atlantic or Pacific Ocean, making it one of the most exploited oceans for fisheries to thrive in.

Waste & Impact

Small Countries like Sri Lanka rely heavily on the fishing industry and have almost 500,000 people employed in this sector. In 2025, the National Aquatic Resources Research and Development Agency reported that Sri Lanka was having a 40% loss in their fish harvest quality. This was particularly due to having overfished boats out in the ocean for a longer period of time, as well as having fewer crew to attend to the fish, thereby reducing the quality of the fish. This can put lots of lives at risk from disease, as well as harm to the benthic environment in the ocean.

Challenges in Indian Ocean Fisheries

Fisheries Regulation

In the vast expanse of the ocean — especially the high seas — regulating fishing activities becomes increasingly difficult, particularly when targeting species like squid or sharks. Enforcement agencies face significant challenges, as investigations require extensive time, resources, and coordination across borders. Smaller target species often go unnoticed due to lower consumer demand, making them vulnerable to unmonitored exploitation and ecological decline.

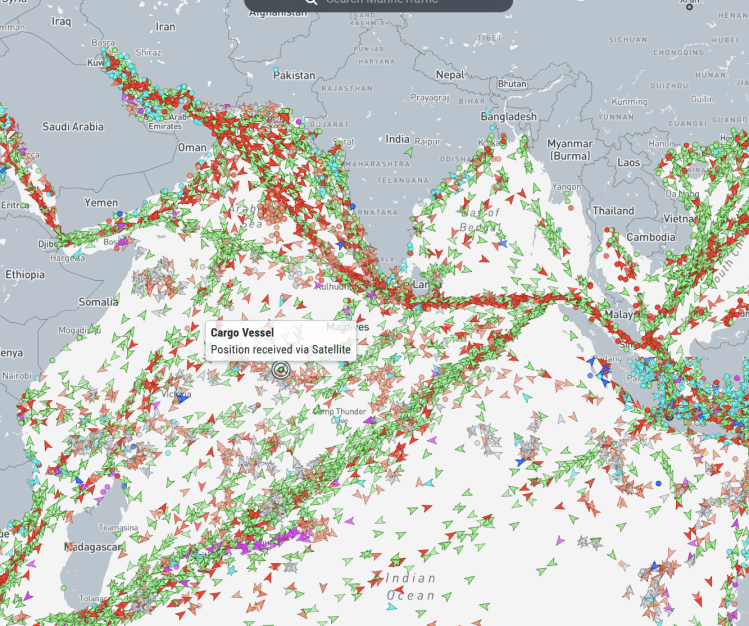

According to the Global Fishing Watch, 75% of industrial fishing vessels are not picked up by their monitoring systems. Many shark species in the Indian Ocean are becoming critically endangered due to being caught as byproducts of tuna fisheries. When critical data — such as vessel navigation routes, harvest totals, and onboard activities — are not consistently tracked, enforcement agencies face major blind spots. This lack of transparency makes it difficult to assess compliance, detect illegal fishing, or even establish jurisdiction. In the Indian Ocean’s high seas and transboundary zones, the absence of reliable information undermines efforts to manage fish stocks sustainably and protect vulnerable marine ecosystems — threatening both biodiversity and the livelihoods of coastal communities.

Poor Waste Management aboard Vessels

In the Indian Ocean, waste management aboard fishing vessels is often overlooked. Fishing vessels often collect untreated bilge water, which is a residue of fuel, seafloor debris, and cleaning chemicals. This mixture is often released into the ocean without proper treatment, resulting in pollution of coastal waters and damage to sensitive benthic ecosystems, particularly in biodiverse zones such as coral reefs and mangrove areas found along the coasts of East Africa, India, and Sri Lanka.

Fishing vessels often discard fish carcasses and byproducts like fins, heads, and guts directly into the ocean, treating them as waste under standard fishing guidelines. While organic, these materials can disrupt ecosystems by depleting oxygen levels and attracting non-native scavenger species, which may destabilize local food chains in the Indian Ocean. These practices highlight a broader challenge: the lack of structured waste management systems at sea. In the absence of proper infrastructure and regional oversight, circular economy principles — such as converting waste into fishmeal or fertilizer — remain underutilized. As a result, the Indian Ocean continues to suffer from linear disposal practices that undermine sustainability and miss opportunities to regenerate marine ecosystems.

When it comes to plastic pollution, discarded fishing nets are the ocean’s most insidious offenders. Most vessels lack tracking systems for their gear, so when nets are lost at sea, they’re rarely recovered.

With an estimated 740,000 kilometers of fishing line vanishing into the ocean each year — enough to circle the Earth nearly 18 times — projections suggest that at this rate, fishing nets could blanket the entire planet within just 65 years. In the Indian Ocean, this contributes to ghost fishing, entanglement of endangered species like sea turtles and sharks leading to potential degradation of coral reefs and benthic habitats

Illegal, Unreported, Unregulated (IUU) fishing

Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated (IUU) fishing is widespread across the Indian Ocean, particularly targeting high-demand species like tuna and shrimp. This unsustainable pressure has led to the depletion of fish stocks in several areas, degradation of marine habitats, and growing threats to regional food security in regions like India, Madagascar, and Kenya, according to the 2023 WWF report.

IUU fishing vessels are notoriously difficult to locate, largely because operators can switch off tracking systems at will — rendering them invisible to radar and satellite surveillance. This deliberate evasion creates blind spots in monitoring efforts. Compounding the challenge is the vastness of the Indian Ocean, which spans millions of square kilometers and borders numerous countries, many of which lack the resources to maintain large-scale patrol units. As a result, investigating and intercepting every vessel suspected of IUU activity becomes a daunting task, leaving critical gaps in enforcement and ocean governance.

Circular Economy Solutions for Indian Ocean Fisheries

Sustainable Aquaculture

Sustainable aquaculture systems are designed to minimize environmental impact while maintaining healthy fish stocks. While aquaculture is heavily used by India, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Africa, the an interest in systems that reduce environmental harm.

One key approach involves the use of recycled water, which helps conserve resources and maintain stable conditions in breeding environments. This would be useful when implemented in regions like the Arabian Sea, where the air is arid along coastal zones.

To further enhance ecological balance, these systems often incorporate native species such as seaweed and shellfish. These organisms naturally absorb excess nutrients and waste produced by the fish, effectively acting as biological filters. This method, known as Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA), mimics natural ecosystems by creating a closed-loop system where waste from one species becomes a resource for another — promoting cleaner water, healthier fish, and a more circular, regenerative aquaculture model.

As overfishing and climate change advances, increasing efforts in a sustainable aquaculture in the Indian Ocean offer a pathway to long term economic opportunity and ecological restoration.

Gear Recycling and Fish Waste Utilization

Gear Recycling and Fish Waste Utilization are important steps towards reducing pollution and regeneration marine ecosystems. In the Indian Ocean, fishing nets and fishing lines are converted into plastic pellets for future gear use. In India and East Africa, recycling efforts have turned fishing nets into nylon-made carpets and construction material for making houses.

Additionally, fish byproducts such as heads, guts, and fins are increasingly being converted into fertilizer or feed, rather than discarded at sea. This is an increasing practice in some states in India, such as Kerala and Tamil Nadu, as well as small-scale fisheries in Sri Lanka.

One-time financial support scheme

The One-Time Financial Support Scheme, initiated by the Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change (MoEF&CC), aims to bolster recycling infrastructure by supporting the establishment of dedicated waste recycling plants. These facilities are designed to tackle the growing accumulation of marine waste — including discarded fishing lines, hooks, and other gear — which are found mainly in regions like the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea.

Beyond its environmental benefits, the initiative also holds significant social value. By creating local employment opportunities and fostering public awareness around responsible waste management, it empowers coastal communities to become active stewards of marine sustainability. In the long term, this effort lays the groundwork for a robust circular economy in the Indian Ocean region by strengthening regional capacity to manage marine waste

Transparency in Vessel Tracking

Transparency-based vessel tracking systems is a broad approach to help improve ocean governance on the whole. There are different types of tracking systems:

Automatic Identification System (AIS) – This system is commonly used on fishing vessels to monitor speed, course, and position. The AIS data is often visible on Global Fishing Watch and MarineTraffic. In 2025, AIS data was shown to aid in the recovery of lost or discarded fishing gear in the sea by tracking the locations of nearby fishing vessels.

Vessel Monitoring System (VMS) – A satellite-based system used by fisheries authorities to track vessel location, speed, and activity in near real-time — essential for enforcing rules, curbing illegal fishing, and managing resources sustainably.

In 2017, Indonesia became the first country to publicly release its VMS data, which included detailed information on vessel locations and commercial fishing activity. This unprecedented move significantly enhanced transparency and enforcement capacity, enabling authorities to track down numerous IUU (Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated) fishing incidents. It also helped uncover previously unreported cases of illegal vessels being sunk, as part of intensified maritime patrols and anti-poaching campaigns.

For future vessel tracking, combining GPS technology with AIS and VMS systems would better amplify the whereabouts and course of ships in real-time. Visualization would also increase and encourage regular supervision to take place.

Marine Protected Areas (MPA)

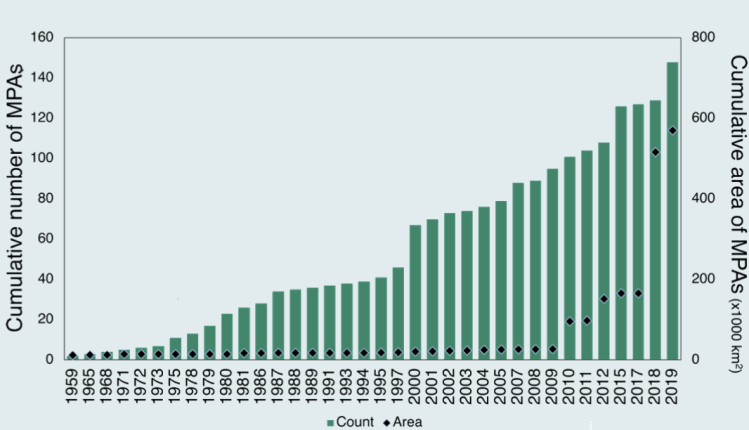

Since the early 2000s, Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) have expanded significantly, now covering approximately 6.35% of the Earth’s surface. In the Indian Ocean, MPAs play a vital role in restoring ecological balance and supporting sustainable fisheries — aligning closely with the principles of a circular economy.

MPAs allow fish stocks to naturally replenish by reducing human pressure in designated zones. This regenerative approach mirrors circular economy ideals, where resources are allowed to renew rather than being exploited to the point of depletion. By protecting breeding grounds and migratory corridors, MPAs ensure long-term productivity of fisheries without relying on constant extraction.

The Chagos Archipelago Marine Protected Area in the British Indian Ocean Territory was created in 2010. It was made to protect key species such as tuna, sharks, and shrimps from fishing practices. As a result, fish stocks were allowed to recover and now it acts as a safe hub for diverse species of fish populations to migrate there for sanctuary or breeding.

MPAs serve as vital breeding grounds for diverse marine species and function as migratory corridors, supporting the natural life cycles of fish and other wildlife. By safeguarding these critical habitats, MPAs enable a long-term strategy for sustainable fishing — one that reduces exploitation and allows ecosystems to regenerate and thrive.

Conclusion

The major challenges facing Indian Ocean fisheries — from illegal fishing and poor waste management to weak enforcement and declining fish stocks. It also highlighted circular economy solutions like sustainable aquaculture, Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), and vessel tracking systems that offer hope for recovery. Countries like India and Indonesia are already taking action through policy and innovation. For everyday readers, the message is simple: choose sustainable seafood, reduce plastic use, and support ocean-friendly policies. Together, informed choices and collective action can help restore the Indian Ocean’s health and secure its future for generations to come.